My earliest exposure to Philippine films is in the early 1980s when I watched a fantasy-adventure film, ‘Kamakalawa’ at the cinema in my hometown. The film featured, among other things, exotic locales and a bunch of midgets. As I remember, throughout the 80s, only two Philippine films were released commercially in Malaysia. Besides Kamakalawa, another film which I also happened to watch was ‘Broken Marriage’, released with the Malay title, ‘Keretakkan Perkahwinan’ (featuring top stars Vilma Santos and Christopher De Leon). In ‘Broken Marriage’, I particularly remember the main protagonists’ intense quarrels that made my head spin, for the film was poorly dubbed in Malay.

In the mid-90s, our TV channel RTM had a slot called Teater ASEAN devoted to screening Southeast Asian films (particularly from Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines). So, I watched some contemporary Philippine films on offer. But, the ones screened via the slot were inane, escapist entertainments, nonetheless. My further acquaintance with Philippine cinema was through reading. I began to familiarise myself with some well-known directors such as Ishmael Bernal, Lino Brocka, Eddie Romero, and Mike De Leon, among others. Only then did I know that the aforementioned ‘Broken Marriage’ was directed by Ishmael Bernal, one of the Philippines’ acclaimed directors.

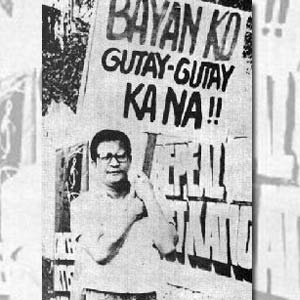

My exploration of academic film studies led me to Bernal’s other works such as ‘Relasyon’ and ‘Himal’. I was also exposed to works by another prominent director, the late Lino Brocka. Brocka directed almost 50 films in a career spanning 20 years. Some of his works that have truly intrigued me are ‘Weighed but Found Wanting’ (1974), ‘Manila: In the Claws of Neon’ (1976), ‘Insiang’ (1978), ‘Jaguar’ (1979), ‘Bayan Ko’ [This is My Country] (1984), and ‘Fight for Us’. Despite the constraints of commercial film industry and draconian censorship rule under Marcos, Brocka triumphed in making half a dozen films of great power and impact. Brocka’s depiction of poverty and political resistance situated him in conflict with the oppressive regime of former President (Marcos), who attempted to ban some of his films. For instance, ‘Bayan Ko’ which was nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes aroused much controversy. Brocka had to smuggle the print out of the country for the screening at Cannes, causing the furious Marcos regime to revoke Brocka’s citizenship.

My exploration of academic film studies led me to Bernal’s other works such as ‘Relasyon’ and ‘Himal’. I was also exposed to works by another prominent director, the late Lino Brocka. Brocka directed almost 50 films in a career spanning 20 years. Some of his works that have truly intrigued me are ‘Weighed but Found Wanting’ (1974), ‘Manila: In the Claws of Neon’ (1976), ‘Insiang’ (1978), ‘Jaguar’ (1979), ‘Bayan Ko’ [This is My Country] (1984), and ‘Fight for Us’. Despite the constraints of commercial film industry and draconian censorship rule under Marcos, Brocka triumphed in making half a dozen films of great power and impact. Brocka’s depiction of poverty and political resistance situated him in conflict with the oppressive regime of former President (Marcos), who attempted to ban some of his films. For instance, ‘Bayan Ko’ which was nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes aroused much controversy. Brocka had to smuggle the print out of the country for the screening at Cannes, causing the furious Marcos regime to revoke Brocka’s citizenship.

Indeed, being a socially (and politically) conscious filmmaker, Brocka often portrays the ugly and dark side of the Philippines (especially Manila), and the hardships of its people beset by poverty, violence and corruption. Brocka’s films are invariably rich in stark imagery, stunningly deployed to evoke sense of filthiness and disgust. That’s the beauty of Brocka’s works – his ability to ‘aestheticise’ the filth and heinousness makes his films powerful visually and viscerally. For example, look at the opening scene of Insiang as we’re shown the squalid slaughterhouse in which pigs are being gutted in a gruesome manner. Whilst the graphic footage prepares viewers for what is to come, it certainly invokes feelings of disgust and distaste.

Brocka’s earlier films such as ‘Wanted: Perfect Mother’ (1970), ‘Santiago’ (1970) and ‘Stardoom’ (1971) appealed to mass audiences and raked in box-office. Feeling disgruntled with crass commercialism, Brocka embarked on making arthouse films that addressed gritty social issues. In 1974, Brocka made ‘Weighed but Found Wanting’ about a teenage boy from a broken family who turns to a leper and a deranged woman (traumatised by an unwanted abortion) for solace. Though working within some conventions of a melodrama, the film is an unflinching indictment of moral and religious prejudice against social outcasts in a rural enclave. The film not only swept many FAMAS (Filipino Academy of Movie Arts and Sciences) awards, but also attained enormous commercial success.

Brocka’s earlier films such as ‘Wanted: Perfect Mother’ (1970), ‘Santiago’ (1970) and ‘Stardoom’ (1971) appealed to mass audiences and raked in box-office. Feeling disgruntled with crass commercialism, Brocka embarked on making arthouse films that addressed gritty social issues. In 1974, Brocka made ‘Weighed but Found Wanting’ about a teenage boy from a broken family who turns to a leper and a deranged woman (traumatised by an unwanted abortion) for solace. Though working within some conventions of a melodrama, the film is an unflinching indictment of moral and religious prejudice against social outcasts in a rural enclave. The film not only swept many FAMAS (Filipino Academy of Movie Arts and Sciences) awards, but also attained enormous commercial success.

My most favourite of his work, ‘Manila: In the Claws of Neon’ is a gritty and realistic odyssey of a village boy who arrives in the violent-ridden Manila to search for his childhood sweetheart who is now a prostitute. Brocka brilliantly showcases the squalor and decay of Manila, saturating the whole film with dark tones and textures. Manila amalgamates diverse styles and approaches from American noir, Italian neo-realism and Philippine melodramatic tradition. The film invites us to the nocturnal underground of the city where prostitutes ply their trade. My favourite scene: the boy takes vengeance into his own hands by convulsively running amok and brutally murdering the elderly Chinese whorehouse owner.

Many of Brocka’s works feature anti-hero narratives. His protagonists’ futile attempts to confront their predicaments individually often resort to violence as the ultimate resolution. Insiang is a tragic melodrama that explores a tumultuous relationship between a teenage girl and her widowed mother who live in a notorious Manila slum area. The tragedy with which the story deals seems Shakespearean; the girl is raped by her mother’s lover, where she finally metes out her revenge. The noirish ‘Jaguar’ deals with a worker’s subservience to his boss, resulting in his frenzied revengeful killing of his lover’s kidnapper, tormentor and murderer. The bravura ‘Bayan Ko’ focuses upon a disillusioned print-shop worker who, ensnared by economic and social circumstances, hurls himself into a downward spiral of crime and violence; the story itself is set against the backdrop of the 1983 assassination of Benigno Aquino, president Marcos’ fiercest opponent.

Many of Brocka’s works feature anti-hero narratives. His protagonists’ futile attempts to confront their predicaments individually often resort to violence as the ultimate resolution. Insiang is a tragic melodrama that explores a tumultuous relationship between a teenage girl and her widowed mother who live in a notorious Manila slum area. The tragedy with which the story deals seems Shakespearean; the girl is raped by her mother’s lover, where she finally metes out her revenge. The noirish ‘Jaguar’ deals with a worker’s subservience to his boss, resulting in his frenzied revengeful killing of his lover’s kidnapper, tormentor and murderer. The bravura ‘Bayan Ko’ focuses upon a disillusioned print-shop worker who, ensnared by economic and social circumstances, hurls himself into a downward spiral of crime and violence; the story itself is set against the backdrop of the 1983 assassination of Benigno Aquino, president Marcos’ fiercest opponent.

Brocka’s sudden death in a car crash in 1991 shocked the whole nation and was a great loss to Philippine cinema. Brocka was posthumously honoured as National Artist for Film in 1997. Brocka’s legacy seems alive as evident in the works of contemporary independent directors such as John Torres, Adolfo B. Alix Jr., Lav Diaz, Martin Raya, and Brillante Mendoza, among others. These directors have acknowledged that their works, to a certain extent, have been influenced by Brocka’s works. I notice that Brillante Mendoza’s works, in particular, bear some striking resemblance with Brocka’s. As is the case with Brocka, Mendoza’s films also sardonically expose humanistic and moralistic ironies in the predominantly Roman Catholic society. Brocka’s works oscillate between melodrama and neo-realism, whereas Mendoza’s nose-to-the-ground aesthetic (such as his raw, handheld camerawork and minimal editing) renders a certain degree of objectivity.

Indeed, Mendoza has a real knack for digital filmmaking. Thus, most of Mendoza’s films are very low-budget works. In fact, most of his films haven’t been released commercially due to financial constraints. But, most of his films have garnered international acclaim at film festivals around the world, ranging from Singapore to Cannes. Some of his critically-acclaimed films are ‘The Masseur’, ‘Foster Child’, ‘Slingshot’, ‘Serbis’, ‘Kinatay’ and ‘Lola’, among others. His most controversial work, ‘Kinatay’ won him the Best Director award at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival. Cheered and hissed at Cannes Film Festival, ‘Kinatay’ drew critical reactions and backlashes. American critic Roger Ebert, in his review of the film, harshly pronounces ‘Kinatay’ as the worst film ever screened at Cannes.

Indeed, Mendoza has a real knack for digital filmmaking. Thus, most of Mendoza’s films are very low-budget works. In fact, most of his films haven’t been released commercially due to financial constraints. But, most of his films have garnered international acclaim at film festivals around the world, ranging from Singapore to Cannes. Some of his critically-acclaimed films are ‘The Masseur’, ‘Foster Child’, ‘Slingshot’, ‘Serbis’, ‘Kinatay’ and ‘Lola’, among others. His most controversial work, ‘Kinatay’ won him the Best Director award at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival. Cheered and hissed at Cannes Film Festival, ‘Kinatay’ drew critical reactions and backlashes. American critic Roger Ebert, in his review of the film, harshly pronounces ‘Kinatay’ as the worst film ever screened at Cannes.

‘Kinatay’ is a pulsating cinematic ride following a day in the life of a financially-desperate, fledgling police officer who gets caught up in the rape and murder of a prostitute. The film features a lengthy scene shot from inside a moving van as corrupt police officers torture and beat the prostitute, and go on to rape, stab and dismember her with blunt kitchen knives, before disposing of the body parts across Manila. The film’s petrifying power may put off some viewers, especially those without the patience and stomach to endure (unfortunately Roger Ebert happens to be one of them). Derided for its ‘brutal nastiness,’ ‘Kinatay’ has also been criticised for its allegedly ‘shoddy’ filmmaking that eschews production values. It seems necessary for the film, with its inquisitive camera, to create the intensely dark, sinister and claustrophobic atmosphere, making us experience exactly the protagonist’s alarming sensibilities to sights, sounds and feelings throughout the nightmarish ride. This is enhanced by Mendoza’s handheld camera, permitting the disturbing ride to unfold in actual time; our tension, anxiety and suffocation escalate, as we hear the woman’s agonising screams and the cacophony of street noise.

Mendoza’s earlier film, ‘Slingshot’ (2007) is a snappy, harsh slice of life set among a group of Manila pickpockets. Using many non-professional actors and filming on the teeming streets of Manila, Mendoza’s visual evokes sense of uncanny authenticity and truthfulness. This is evident in the film’s opening scene, as the camera works its way through a squatter slum in the seedy part of Manila, providing the film with a ‘street’ feel. Though a work of fiction, ‘Slingshot’ could easily be mistaken for a documentary. Interestingly, the film also rejects a central narrative or decent plotting, whilst defying the schematic three-act structure (of course, this might irk any pedantic screenwriting gurus and students).

Mendoza’s earlier film, ‘Slingshot’ (2007) is a snappy, harsh slice of life set among a group of Manila pickpockets. Using many non-professional actors and filming on the teeming streets of Manila, Mendoza’s visual evokes sense of uncanny authenticity and truthfulness. This is evident in the film’s opening scene, as the camera works its way through a squatter slum in the seedy part of Manila, providing the film with a ‘street’ feel. Though a work of fiction, ‘Slingshot’ could easily be mistaken for a documentary. Interestingly, the film also rejects a central narrative or decent plotting, whilst defying the schematic three-act structure (of course, this might irk any pedantic screenwriting gurus and students).

‘Serbis’ (2008), my most favourite of his work, takes place in an old movie theatre in Angeles City. The film revolves around a family who runs a dilapidated cinema which screens 70s porn movies. The cinema itself serves more than a metaphor for the disintegration of the family unit, or a crumbling world the family members inhabit. It’s an abode, a recreational rendezvous, a business, and a shelter for the family and its lecherous clientele. Mendoza’s critical observation of the society culminates in the film’s finale when he shows the religious masses passing by the cinema. The good thing is that, in ‘Serbis’ and other films, Mendoza always addresses his social statements and critiques by means of visuals.

Mendoza’s latest work, ‘Lola’ (2010) is unbearably poignant. It is about two grandmothers who must encounter the repercussions of a crime involving their grandsons – one of whom is the murder victim and the other the suspect. They wend their way around Manila trying to raise money for the funeral and the trial respectively. Both Mendoza’s technique and the actors’ performances manage to convey a sense of uneasiness whether we’re drawn into the urgencies of the two elderly women’s harrowed lives, or we’re dragged to contemplate their lives of quiet desperation. Despite its ‘unfussy’ camerawork, ‘Lola’ is still visually arresting. Water, for example, as conjured by scenes showing rainstorm and riverside shanties, becomes the film’s recurrent imagery.

Mendoza’s latest work, ‘Lola’ (2010) is unbearably poignant. It is about two grandmothers who must encounter the repercussions of a crime involving their grandsons – one of whom is the murder victim and the other the suspect. They wend their way around Manila trying to raise money for the funeral and the trial respectively. Both Mendoza’s technique and the actors’ performances manage to convey a sense of uneasiness whether we’re drawn into the urgencies of the two elderly women’s harrowed lives, or we’re dragged to contemplate their lives of quiet desperation. Despite its ‘unfussy’ camerawork, ‘Lola’ is still visually arresting. Water, for example, as conjured by scenes showing rainstorm and riverside shanties, becomes the film’s recurrent imagery.

Brocka and Mendoza offer no apologies for making viewers uneasy with their hard-hitting explorations of the seamier, darker side of life in the Philippines. Both are also directors with an excellent grasp of the (film) medium, as aesthetically, their approaches ascribe sense of unvarnished truth to their works. Having said that, their films refrain themselves from debunking the ‘official image’ of the Philippines, as normally sanctioned by the state. Such ‘official image’ can be found in many commercially-made, meretricious Philippine films, as well as their dull, soporific TV soap operas.

Reprinted with permission of the author.

Featured image credit: Raymund Gerard / Youtube

I like Brocka. I can’t decide yet on Mendoza. I honestly did not like “Kinatay”. My fave of all I’ve seen is “Lola” — breaks my heart.

I think they all bring a little more flavour to the scene. We haven’t seen Kinatay yet, but Lola was certainly a heartbreaker. Not an easy film to watch, like many other films in this movement, but the searing honesty that’s difficult to face is necessary viewing.

I really like what you wrote. May I ask for a reblog one of these days?